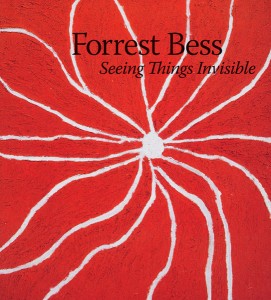

This Sunday the Forrest Bess:Seeing Things Invisible exhibition opens at the Neuberger Museum—the final stop on a tour that has included The Menil Collection in Texas and the Hammer Museum in LA. The exhibition catalog’s designer, Don Quaintance, shares a guest post with us today on his fellow Texan’s work. We hope that, given its roots in the Gulf Coast wetlands, the exhibition will remind frozen New Yorkers of warmer climes.

This Sunday the Forrest Bess:Seeing Things Invisible exhibition opens at the Neuberger Museum—the final stop on a tour that has included The Menil Collection in Texas and the Hammer Museum in LA. The exhibition catalog’s designer, Don Quaintance, shares a guest post with us today on his fellow Texan’s work. We hope that, given its roots in the Gulf Coast wetlands, the exhibition will remind frozen New Yorkers of warmer climes.

Don Quaintance—

Forrest Bess’s work spans categories every which way. He was an outsider artist who also showed with the toast of New York’s avant-garde in six solo shows at the prestigious Betty Parsons Gallery. He was a reclusive hermit running a bait camp near East Matagorda Bay in Texas, yet helped found cooperative alternative art spaces in big city Houston in the 1940s. He was a strapping rugged fisherman who was also openly queer to many friends and associates. He was a Texas oilfield worker who corresponded regularly with art historian Meyer Schapiro. He was a self-absorbed visionary but also a naturalist deeply in touch with the physicality of the Gulf Coast wetlands. His paintings are abstractions that often border on being landscapes.

However, Bess’s paintings are of a piece. Once one has seen a few, they are readily recognizable. And it’s not just because the naked driftwood frames—with the crude unmitered corners—are a dead giveaway. Nope, it’s the paintings themselves. As Bess stated over and over, the images sprang from his dreams, though not necessarily from sleep; sometimes they were waking visions. One might get the idea from all this background that the works were spontaneously painted, but like most of Franz Kline’s so-called “action paintings,” they are based on careful preliminary studies.

Oddly, though Bess created what he called a “Primer of Basic Primordial Symbolism” (an amended amalgamation appears in this book), often the task of matching up the specific symbols from this lexicon with the images in the paintings is a daunting one. The symbols spring from an unlimited grab bag of cultures and psychological sources, yet Bess’s interpretations can border on the completely invented. Titles sometimes help inform the viewer, but in other cases they baffle: Tab Tied to the Moon Film, for example. Huh?

Oddly, though Bess created what he called a “Primer of Basic Primordial Symbolism” (an amended amalgamation appears in this book), often the task of matching up the specific symbols from this lexicon with the images in the paintings is a daunting one. The symbols spring from an unlimited grab bag of cultures and psychological sources, yet Bess’s interpretations can border on the completely invented. Titles sometimes help inform the viewer, but in other cases they baffle: Tab Tied to the Moon Film, for example. Huh?

What the viewer almost always sees is a visceral impasto, a color palette than often seems untethered from any recognizable style, a sense of horizon line undercut by an equal sensation of objects afloat in amorphous space. The small, sometimes tiny, scale of the works provides no reasonable basis for their ability to hold a massive presence on the wall.

These qualities drew visitors to Bess’s Chinquapin Bayou bait camp to seek out the maker of these images. One such trip in 1958 involved a powerhouse trio: the prolific photographer Eve Arnold, the pioneer curator Jermayne MacAgy, and the all-purpose, always purposeful patron Dominique de Menil. They came away with a few paintings, but perhaps more importantly with the measure of this man, a homegrown artist.

Yes, Bess’s word “primordial” fits, like the razor-sharp fish-fileting knife into in his pocket sheath. The same one he used on self-surgery on his genitals in an attempt to achieve a hermaphroditic nirvana. But that’s another story. It’s both tangential and integral to the work—there’s that dichotomy again—and one that is thoroughly investigated by Robert Gober’s contribution to this book.

Yes, Bess’s word “primordial” fits, like the razor-sharp fish-fileting knife into in his pocket sheath. The same one he used on self-surgery on his genitals in an attempt to achieve a hermaphroditic nirvana. But that’s another story. It’s both tangential and integral to the work—there’s that dichotomy again—and one that is thoroughly investigated by Robert Gober’s contribution to this book.

Bess, yep, he’s a Texas original.

Don Quaintance, like Forrest Bess, is a native-born Texan. Don is a graphic designer and the principal of Public Address Design, Houston, whose recent book designs include Forrest Bess: Seeing Things Invisible (Menil Collection, 2013), Robert Motherwell: Early Collages (Guggenheim Museum, 2013), and Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés (Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2009). He is an author, whose essays have been published in such books as Joseph Cornell/Marcel Duchamp… in resonance (Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1998) and Peggy Guggenheim & Frederick Kiesler: The Story of Art of This Century (Guggenheim Museum, 2005).

Ep. 134—The Therapeutic Benefits of Reading Greek Tragedy

Ep. 134—The Therapeutic Benefits of Reading Greek Tragedy